|

11/15/2022 1 Comment Rosemary Monograph

History: Rosemary has been used for thousands of years and is surrounded by symbolism. It is mentioned in Cuneiform tablets dating to 5000 BCE, and in reference to ancient Egyptian burial rites. The Ancient Greeks and Romans mentioned rosemary in the writings of Pliny the Elder and Dioscorides. Rosemary appeared in China during the Han dynasty (220 CE) and was grown in Britain in the 8th century, as an herb cultivated in monastic gardens. Rosemary has long been known as the herb of remembrance, with references strewn throughout literature including Shakespeare's Hamlet. We see evidence of its use for cerebral stimulation in the writings of Nicholas Culpeper. In his 17th-century herbal, Culpeper writes… "The decoction thereof in wine, helps the cold distillation of rheums into the eyes, and all other cold diseases of the head and brain, as the giddiness or swimmings therein, drowsiness or dulness of the mind and senses like a stupidness, the dumb palsy, or loss of speech, the lethargy, and falling-sickness, to be both drank, and the temples bathed therewith." Maude Grieve writes that rosemary was often used to adorn both weddings and funerals and that it was burned to ward off illness during the plague and in sick chambers. In more recent times, Juliette de Baircli Levy writes that rosemary was a favorite of both the Gypsies and the Arabs, whom she traveled and learned the use of herbs from. Levy used rosemary as a heart tonic, to promote the flow of breastmilk, to prevent nightmares in children, for high blood pressure, headaches, and “all nervous ailments”. Throughout the centuries, rosemary has been used as a hair and skin tonic. It is credited with preventing and treating hair loss, strengthening hair, and keeping skin youthful and healthy. It is a key herb in the famous Queen of Hungary’s water, which some sources claim was used as a skin treatment by Catherine of Hungary, and others claim was used to treat her aching joints.

Tissue states: damp, lax, stagnation Properties: antidepressant, antiseptic, circulatory stimulant, carminative, cerebral tonic, expectorant, antirheumatic, antioxidant, anxiolytic Constituents: tannins, resin, bitter principle, volatile oil (borneol, bornyl acetate, dipentene, eucalyptol, camphene) Key uses: Rosemary is stimulating and strengthening to the circulatory system, the nervous system, and the digestive system. It can be used for low energy, memory problems, headaches, aching joints, sluggish digestion, and as a heart and circulatory tonic. Its antiseptic and astringent properties make it useful externally as a wound herb, both for preventing infection and promoting healing. Its warming, drying, and expectorant properties make it useful for congestion in the upper respiratory system.

He goes on to say that rosemary stimulates metabolism, “enhancing the burning and consumption of blood sugars and fats”. This makes rosemary useful in cases of metabolic syndrome and diabetes. Rosemary may also be useful in cases of congestive heart failure, high blood pressure, and cardiac edema. It serves both as a circulatory tonic and also stimulates and opens blood vessels and capillaries, helping to clear congealed blood. It can improve circulation to the limbs and stimulate nerves, helping to restore function. Rosemary’s ability to increase circulation to the brain, bringing blood and oxygen to the cells makes it useful for headaches. Sometimes an external application of the infused oil or salve is enough. Dr. Christopher recommends a tea with rosemary, sage, and peppermint, taken every hour or two until relief. For migraines, he recommends a formula with equal parts rosemary, vervain, skullcap, and wood betony taken over several weeks. Studies: In a 2011 study published is the journal Chemico-Biological Interactions (Ferlemi, Katsikoudi, Kontogianni, Kellici, Iatrou, Lamari, Tzakos, and Margarity) researchers tested the effects of rosemary tea on mice and their ability to perform anxiety and depression inducing activities. In this study, mice were divided into two groups. A control group was given food and water, the other group had rosemary infusion added to the diet. After 25 days both groups were tested with a maze, swimming, and cognitive tests. Results indicated a significant anxiolytic and antidepressant effect on the mice in the rosemary group. In a 2004 study published in Life Sciences (Amin and Hamza) water extracts of rosemary, hibiscus, and sage were tested in their ability to protect the liver against the toxic effects of azathioprine (AZP). For this study, rats were divided into 5 groups. The first group received a dose of AZP on the first day. Groups 2, 3, and 4 received infusions of either rosemary, hibiscus, or sage daily for 5 weeks before receiving AZP one hour later. The last group was the control group. Blood samples were taken to measure the elevation of liver enzymes ALT and AST. This study concluded that “pretreatment with water extract of any of the three herbs used in this study (HA, RO, or SO) blocked the AZP-induced elevation of serum ALT and AST activities”. The authors go on to say that the study “demonstrates that all herbs examined in this study restore the levels of AST and ALT to normal and can be regarded as good protecting agents against the toxicity of AZP as they all improve the GSH and lipid peroxidation along with AST and ALT levels”. Dosage and method of delivery: Infusion of the leaves as a mild tea, 3 cups a day. Tincture of the dried leaves (1:5, 65%, 10% glycerine), 10 drops to 3 MLS. up to 3 times a day. Capsules, 500-1500 mg up to 3 times a day. Soxhlet extract of the freshly dried leaves, 3 to 5 drops up to 3 times a day. Topical preparations of infused oil, salve, hydrosol, or diluted essential oil.

Cautions and considerations: none known

References: Easley, T., and Horne, S. (2016). The Modern Herbal Dispensatory. California: North Atlantic Books Wood, M. (2008). The Earthwise Herbal (Old World edition). Berkeley, California: North Atlantic Books. Christopher, J. R. (2010). Herb Syllabus. Springville, Utah. Christopher Publications. Culpeper, N. (1990 reprint). Culpeper’s Complete Herbal & English Physician. Illinois: Meyerbooks. Grieve, M. (1982 reprint). A Modern Herbal. New York: Dover Publications. Storl, W. (2012) The Herbal Lore of Wise Women and Wortcunners. Berkeley, California. North Atlantic Books. Levy, J. (1996). Common Herbs for Natural Health. Woodstock, New York. Ash Tree Publishing. Wikipedia, [Rosemary]. Retrieved August 1, 2020, from https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Rosemary Ferlemi, A., Katsikoudi, A., Kontogianni, V., Kellici, T, Iatrou, G., Lamari, F., Tzakos, A., Margarity, M., (2011). Rosemary tea consumption results to anxiolytic- and anti-depressant-like behavior of adult male mice and inhibits all cerebral aria and liver cholinesterase activity; phytochemical investigation and in silico studies [Chemico-Biological Interactions]. Retrieved August 3, 2020, from https://scihub.to/10.1016/j.cbi.2015.04.013 Amin, A., Hamza, A., (2004). Hepatoprotective effects of Hibiscus, Rosmarinus, and Salvia on azathioprine-induced toxicity in rats [Life Sciences]. Retrieved August 3, 2020, from https://scihub.to/10.1016/j.lfs.2004.09.048

1 Comment

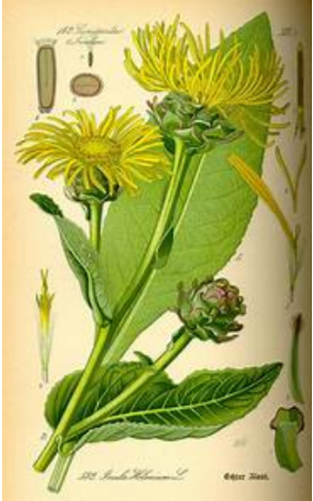

9/22/2022 0 Comments Elecampane MonographBotanical description: Elecampane is an herbaceous perennial plant often growing to 5 feet or taller. The large, erect stalk grows up from a rosette of large ovate leaves. Leaves on the stem are alternate, clasping, and are shorter than the rosette leaves. Flowers are bright yellow with both disc and ray flowers characteristic of the Asteraceae family. The outer, ray flowers are very narrow, almost hair-like. The entire plant is covered with downy hair. Elecampane blooms in late summer. It is found throughout Europe and temperate Asia. It has become naturalized in North America as well. Elecampane is easily cultivated by seed and prefers rich, damp, well-drained soil in full or part sun. Roots are best harvested after 2 to 3 years in the fall or early spring. Parts used: Roots Taste: acrid, bitter, pungent

"fasteneth loose teeth and keeps them from putrefaction, and being drunk is good for spitting of blood, and it removes cramps or convulsions, gout, sciatica, pains in the joints, applied outwardly or inwardly, and is also good for those that ruptured, or have any inward bruise." Its use persisted in Europe through to recent times. As early as 50 years ago elecampane candy could be purchased in England for use against “bad air” (Grieve). In the early 1900’s, Jethro Kloss wrote of elecampane’s use in treating tuberculosis (combined with echinacea). He described it as “warming and strengthening to the lungs, promoting expectoration.” He went on to say “it strengthens, cleanses, and tones up the pulmonary and gastric membranes”. Around the same time its use among the eclectics was documented by Felter in his Eclectic Materia Medica, Pharmacology and Therapeutics. Felter wrote about elecampanes power against respiratory infection and its great use as an expectorant. He writes… "Inula is of greatest service in bronchial irritation, with cough of a persistent, teasing character, with copious expectoration." Key uses: Helps clear phlegm and mucous from the respiratory, urinary, and digestive systems. Prebiotic for beneficial gut bacteria. Helpful for chronic respiratory infection. Useful for coughs, bronchitis and other pulmonary diseases, digestive complaints, and asthma. Clinical uses: As a bitter and an aromatic, elecampane is helpful for digestive complaints like sluggish digestion or indigestion. It is stimulating to digestion and appetite, and helps clear excess mucus from the digestive tract. The inulin content also feeds healthy intestinal flora, thus strengthening digestion. Elecampane shines as a respiratory herb. It is indicated for almost any respiratory condition of an acute or chronic nature. As a respiratory expectorant, elecampane helps to move out excessive mucus. Non-productive coughs become productive and fluid in the lungs is gently expelled and airways are relaxed and opened. Because of this action, elecampane is found to be useful for asthma, pertussis, pneumonia, tuberculosis, and even emphysema. It is safe for children and the elderly, and combines well with other herbs in formula. Matthew Wood writes that elecampane has been used historically for “proud flesh” where a wound is not producing a scab. He describes how using elecampane externally can help old wounds to heal, and that this may also explain why elecampane is so valuable for treating old, chronic infections internally as well. This can be seen when the mucus expelled is green or yellow, indicating bacteria. Elecampane’s use leads to the color changing to white and then clear, showing its effectiveness as an antiseptic. As an emotional medicine, elecampane is a remedy of the heart. It can be helpful in cases of sadness and grief. It is especially indicated in instances of extreme homesickness, as when someone can never return to one’s homeland. Studies: In a 2009 study published in the British Journal of Biomedical Science, researchers studied the antimicrobial effects of Inula helenium against 200 strains of Staphylococcus aureus, including MRSA. Results proved I. helenium to be 100% effective against all strains, including the antibiotic-resistant and sensitive strains. Personal observations: I have personally had great success growing this plant and harvesting the roots for medicine. It is an impressive and beautiful plant in the garden. If given a few years to grow, the roots are big enough to offer up enough medicine for a family’s use for a year from a single plant. I have made fresh root tinctures, elixirs, infused honey, and especially candied elecampane from the freshly dug roots. For the candy, I slice the washed roots thinly and put in a jar, covered with honey. I let them sit for a few weeks. The honey softens the roots, and also infuses with their medicine. Then I gently warm the honey enough to thin it so I can strain out the root slices. I save the honey for adding to teas, or just taking by the spoonful. The root slices are spread on a dehydrator sheet and dried until the honey coating them becomes solid. I put these candied roots in a jar for chewing on whenever someone has a sore throat or just lots of mucus. Elecampane is one of my most used respiratory herbs in both syrups and tincture formulas. I have found it to be reliable for expelling mucus and helping coughs become more productive. I try to never be without this plant, especially during cold and flu season. Cautions and considerations: May cause allergic reactions in people sensitive to the asteraceae family References: Easley, T., and Horne, S. (2016). The Modern Herbal Dispensatory. California: North Atlantic Books Hoffman, D. (2003). Medical Herbalism. Rochester, Vermont. Healing Arts Press. Wood, M. (2008). The Earthwise Herbal (New World edition). Berkeley, California: North) Atlantic Books. Grieve, M. (1982 reprint). A Modern Herbal. New York: Dover Publications. Felter, H. W. (1922). The Eclectic Materia Medica, Pharmacology and Therapeutics. Cincinnati, Oh. Eclectic Medical Publications. Kloss, J. (1939). Back to Eden. O’Shea, S., Lucey, B. (2009) In vitro activity of Inula helenium against clinical Staphylococcus aureus strains including MRSA [British Journal of Biomedical Science]. Retrieved February 2, 2021, from https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/abs/10.1080/09674845.2009.11730271

7/15/2022 0 Comments Saint John's Wort MonographLatin name: Hypericum perforatum Family: Hypericaceae Common names: common Saint John’s wort, perforate Saint John’s wort, devil’s flight (fuga daemonum), bells of Blessed Mother (dzwonki Panny Marii in Polish), blood of Blessed Mother (krewka Matki Boskiej in Polish), herb of St. John (ziele Św. Jana in Polish) Botanical description: Saint John’s wort is an herbaceous perennial in the Hypericum genus, of which there are 400 species around the world. Christopher Hobbs writes, “St. John’s wort is native to Europe, West Asia, North Africa, Madeira and the Azores, and is naturalized in many parts of the world, notably North America and Australia”. Narrow stalks rise from spreading rhizomes and grow up to 3 feet tall. Leaves are opposite, ovate, and are dotted with what appear to be tiny punctures when held up to the light (thus the species name “perforatum”). Small, yellow flowers are regular, five-petaled, with 5 sepals, and many stamens rising from 3 united bundles. The flower buds, when crushed, will produce a red stain. Saint John’s wort spreads by both seed and creeping rhizome.

Hypericum was among the 20 different herbs found at the Biskupin archeological site in Poland, dating back to 550-400 B.C. Evidence suggests that these herbs were used not only for food, but for medicine as well, and for magic. Sophie Hodorowicz Knab writes, “There was also no doubt that these early Slavs had had cults revering plants, animals, and trees and attributed great magic, strength, and power to them”. Matthew Wood writes that in Middle Ages Europe Saint John’s wort and wood betony were “two of the most important remedies for psychiatric problems”, and that both of these herbs “strengthen the enteric brain”, connecting us to our gut instincts. This herb also has a long history of use for depression, wound healing, and pain. It was also a folk remedy for bedwetting and nightmares in children. In Poland at this time, it was traditional to make wreaths from the plant on St. John’s Eve (June 24th) to hang in the window. This was believed to protect from lightning strikes. The plant was also “tucked into crevices and the chimney” to protect a new mother and infant against evil spirits. For the same reason, midwives would place sprigs of hypericum under a new mother’s pillow and around the neck of infants. The name “hypericum” means “over an apparition”, and a common name for hypericum in Europe is “devil’s flight”. This is a reference to the folk belief that spirits were warded off by the plant, and it was carried on the body or hung over the door for protection from spirits.

The term “wort” is an Anglo Saxon word meaning medicinal plant, and the common name refers to Saint John the Baptist, as the tendency for hypericum to bloom around the summer solstice, St. John’s day, associated the saint with this plant. In addition, the red stain produced by the crushed flowers came to represent the blood of St. John. Anne McIntyre writes that “on the night of St John young girls would hang the herb over their doors or sleep with it under their pillows, to foresee their husbands”. Saint John’s wort is still in use among common folk in Europe today. German herbalist Wolf Storl writes that “Swiss peasants massage hands and arms with it when the nerves get inflamed from the strain of milking cows”. In North America, early American herbalist Samual Henry made use of Saint john’s wort in the early 1800s. His writings reference its use for ulcers, menstrual issues, and nervous system issues. In 1922, Felter wrote of the herb’s use for spinal injuries, shocks, and concussions, as well as externally as a vulnerary for bruises, swellings, puncture wounds, sprains, and lacerations.

Constituents: volatile oil, naphthodianthrones (hypericin, pseudohypericin), phloroglucinols (hyperforin), catechins, proanthocyanidins, flavonoids (hyperoside, rutin) Key uses: nerve pain, nerve damage, sprains, strains, wounds (including puncture wounds), mild depression (especially associated with anxiety or digestive issues), shingles, herpes, spinal injuries, fluid retention, incontinence, overactive bladder, painful urination Clinical uses: Nervous System… Jill Stansbury writes that “intensive research shows Hypericum to have broad neurotransmitter effects, including activity on serotonin, GABA, and dopamine pathways”. Clinical studies support the traditional use of Saint John’s wort for mild depression and anxiety, but the mechanism of action is still not fully understood. Also, while it was once thought that hypericin was the active constituent involved in its antidepressant properties (and supplements were standardized for hypericin because of this), it is now known that other constituents are involved as well. Bone and Mills write… "Hypericin was previously thought to be the only active constituent in depression, but more recent interest has focused on other constituents including hyperforin, an unstable compound shown in in vitro and in vivo studies to have antidepressant activity. The flavonoids have also received attention in this context. However, the total extract appears to be more effective than isolated constituents in terms of the antidepressant effect of Hypericum, and most of the data to date suggest that multiple mechanisms exhibited by several groups of active compounds may be involved in the antidepressant action of Hypericum." What we do know is that Saint John’s wort can be helpful for mild depression, seasonal depression, anxiety, and stress. David Hoffman writes that Saint John’s wort is “especially appropriate for use when menopausal changes trigger irritability and anxiety”. Clinical studies support this statement. In addition, Hypericum can help reduce symptoms of PMS, including irritability, anxiety, depression, and headaches. Anne McIntyre writes that its “mood-elevating properties take 2-3 months to produce lasting effects, brought about by the plant’s ability to enhance the effect of neurotransmitters in the brain”. And, as Kathi Keville writes, “unlike many anti-depressant drugs, it does not impair your attention, concentration or reaction time”. We also know that Saint John’s wort is specific to the nerves, able to exhibit an antiviral effect within the nerve endings (thus its usefulness for herpes, shingles, and chicken pox), and able to repair damaged nerves and decrease nerve pain. This may be why it is so useful for back pain and injury, as well as head injury, shock, and concussion. In addition, Saint John’s wort improves memory, cognition, and has a neuroprotective effect. It has been shown to be helpful in cases of Alzheimer’s and dementia-related memory problems. Saint John’s wort’s sedative properties seem to help increase both the quality and quantity of sleep in both animal and human trials. Mills and Bone write, “In an uncontrolled trial with 13 healthy volunteers, a significant increase in nocturnal melatonin plasma concentration was observed after 3 weeks of administration of Hypericum extract (0.5 mg/day TH equivalent)”. As an analgesic, Saint John’s wort may be used both internally and externally (see below) for reducing pain. It can be a useful addition to formulas for neuralgia, inflammation, tension, sciatica, and rheumatism. Kathi Keville likes to combine hypericum in a tincture with muscle relaxants (valerian, hops, passionflower…) to address pain associated with movement.

There also seems to be a beneficial effect in Irritable Bowel Syndrome pain with hypericum use. This has been linked to the connection of stress to IBS flares, and Saint John’s wort’s ability to increase resistance to stress. Kathi Keville writes about using hypericum in formulas for Crohn’s disease in combination with herbs such as chamomile, peppermint, hops, and wild yam to reduce inflammation and pain. She writes that these herbs, “relax the nervous constriction of the digestive muscles and reduce the general tension that can promote bowel problems”. Its antiseptic and antiviral properties make hypericum useful for infections of the GI tract. And its healing properties make it useful for digestive ulcers. Liver… Saint John’s wort stimulates the liver through its ability to increase the activity of liver enzymes, specifically cytochrome P450 enzyme CYP3A4. This results in faster metabolism of waste from the system, but also in the faster removal of medications that are metabolized through this pathway (see cautions below). If medication contraindication isn’t an issue, the liver stimulating properties of hypericum can help to metabolize toxins and metabolic waste, including hormones. Katja Swift of Commonwealth Herbs writes… "Whether you’re making a bunch of adrenaline and cortisol to deal with stress, or you’ve had some sugary treats and there’s a lot of insulin floating around, or even just your regular everyday hormonal cascade – all of it goes to the liver to get broken down and recycled when it’s done. If your liver isn’t up to snuff, hormone imbalance is a common result. St. John’s Wort can help your liver keep up with its to-do list, and give it an extra boost in hormonal crunch time!" Urinary System… Saint John’s wort is a mild diuretic and has an effect on the bladder and urinary system. It may be helpful for such conditions as incontinence, excessive urination, painful urination, and overactive bladder. Wiliam LeSassier has written that is especially helpful for “emotions that influence the bladder”, and so may be indicated when urinary issues seem to be stress-induced. Its help with incontinence may be due to its relaxing effect on the bladder, its role as an antidepressant (there is often a link between depression and incontinence), or both. Hypericum’s diuretic properties also make it useful in cases of fluid retention, gout, and arthritis. However, it has also been used to help children with bedwetting (something diuretics and not usually helpful for). This is due to the plant’s toning effect on the urinary system. Kathi Keville recommends a tincture formula with equal parts Saint John’s wort, milky oats, cornsilk, and plantain. The recommended dosage for this formula is 15 drops three times a day for a 50-pound child.

External… As a topical, Saint John’s wort is one of the most useful plant medicines. Its antiseptic properties make it a great medicine for preventing and treating infection in wounds. This is best done as a bath or soak of a strong infusion. If infection is not an issue, the infused oil or salve is great for easy external application for all manner of bites, stings, rashes, abrasions, inflammation, and pain. Saint John’s wort infused oil can also be a helpful external application for menstrual cramps. As a topical pain remedy, Hypericum alone is often enough for significant pain reduction. It is healing and soothing to nerve endings and anti-inflammatory to the tissues. However, when used in a topical pain formula its effects can be even stronger. For sprains and strains, doing a compress of the infusion, or regular application of the infused oil can reduce swelling and pain and speed healing. The same technique can be used for other types of trauma, including bruises, bumps, and swellings. For neuralgia and other nerve-specific afflictions (such as herpes, chickenpox, and shingles) hypericum can significantly reduce pain levels and speed healing. In these instances, getting the medicine directly into the local tissue is most effective. Its antiviral properties make it one of the most useful remedies for viral infections that affect the nerves and manifest in specific locations in the body. Saint John’s wort tincture, dropped into the ear, can be helpful for swimmer’s ears, where water is trapped inside the ear canal. It is important to use the tincture and not the oil for this purpose. The alcohol of the tincture helps to evaporate the water (while an oil would only trap it) and the hypericum helps to reduce pain and inflammation. Although it can cause photosensitivity when used externally (see cautions below), Saint John’s wort is healing to minor burns and even sunburn. Hypericum is also a useful addition to formulas for varicose veins and hemorrhoids, lending its astringents, toning, and anti-inflammatory properties to the medicine. Homeopathic medicine: In homeopathy, hypericum is known as the “arnica of the nerves” (McIntyre). As such, it is used for trauma to areas of the body rich in nerve fibers, such as the spine, fingers, toes, mouth, and eyes. Often, arnica and hypericum are given together, the first for possible swelling and bruising, and the second for pain and shock.

Capsules: 500 to 1500 mg, 3 to 4 times a day Studies: Hypericum for Perimenopausal Symptoms In a 2009 study published in The Journal of the North American Menopause Society entitled Effects of Hypericum perforatum (St. John's wort) on hot flashes and quality of life in perimenopausal women, researchers tested the effect of 900 mg of ethanolic Saint John’s wort extract given three times a day for three months on the severity and frequency of hot flashes in perimenopausal women. For this double-blind randomized clinical trial forty-seven women between the ages of 40 and 65 who were experiencing three or more hot flashes a day were randomly assigned either the hypericum extract or a placebo. After twelve weeks, the Saint John’s wort group showed slight improvement in hot flashes, but significant improvement in menopause-specific quality of life and significant improvement in sleep quality. The researchers concluded that “Hypericum perforatum may improve quality of life in ways that are important to symptomatic perimenopausal women, but these results need to be confirmed by a larger clinical trial”. Hypericum for Bone Density in Post-Menopausal Women Another study, published in the journal Nutrition Research and Practice in 2015, titled St. John's Wort (Hypericum perforatum) stimulates human osteoblastic MG-63 cell proliferation and attenuates trabecular bone loss induced by ovariectomy, tested the effect of Saint John’s wort extract on postmenopausal osteoporosis. In this study, rats with ovaries removed were given either a 100 or 200 mg/kg/day dose of hypericum (hot ethanol extract, concentrated and freeze dried), β-estradiol-3-benzoate, or placebo. Dosing began two weeks after surgery and continued for six weeks. Results of this study showed “beneficial effects of SJW on MG-63 human osteoblast cell differentiation and proliferation, and also on skeletal tissues in an estrogen-deficient animal model”. The rats treated with Saint John’s wort show significantly higher levels of bone density. The authors concluded that “It is thus conceivable that SJW might be clinically useful and effective in the prevention of bone loss in postmenopausal women”. Hypericum’s Anti-inflammatory and Analgesic Properties In a 2001 study published in the Indian Journal of Experimental Biology, researchers tested the anti-inflammatory and analgesic properties of Hypericum perforatum. Rats that had been injected with a phlogistic agent to induce edema were treated with 100 to 200 mg/kg of standardized 50% aqueous ethanolic extract of Hypericum perforatum. This was compared to mice treated with pentazocine ( 10 mg/kg) and aspirin (25 mg/kg). The authors concluded that the “IHp extract showed significant anti-inflammatory and analgesic activity at both dose levels, in all the paradigms used”. A Review of the literature on Hypericum for Depression In a 2003 article published in the journal Phytomedicine titled, A review of clinical and experimental observations about antidepressant actions and side effects produced by Hypericum perforatum extracts, authors looked at the existing research of Saint John’s wort’s effectiveness and cautions associated with its use as an antidepressant. Both animal and human studies were examined for this article. The authors write… "Hypericum perforatum is an herbaceous perennial plant, also known as “St. John’s wort”, used popularly as a natural antidepressant. Although some clinical and experimental studies suggest it has some properties similar to conventional antidepressants, the proposed mechanism of action seems to be multiple: a non-selective blockade of the reuptake of serotonin, noradrenaline and dopamine; an increase in density of serotonergic and dopaminergic receptors and an increased affinity for GABAergic receptors; moreover, the inhibition of monoaminoxidase enzyme activity has been involved. In any case, the increase of monoamine concentrations in the synaptic cleft resembles several actions exerted by clinically effective antidepressants." The authors also point out some of the side effects of Saint John’s wort in the scientific literature, including…

In considering the above article, the herbal literature tells us that Saint John’s wort is most effective for mild to moderate depression and only if psychiatric medication is not already in use. Severe depression, and especially bipolar, is contraindicated for Hypericum. In addition, its action on the P450 pathway is more of an “effect” than a “side effect”. By this I mean that in the absence of medication that is metabolized through this pathway, the stimulation of P450 can be seen as a beneficial action, helping the body to clear toxins and process hormones and metabolic waste.

A roll-on bottle of infused saint john’s wort oil is a staple in both the medicine cabinet and the travel first aid bag. The roll-on makes the oil easier and less messy to apply, and also limits accidents with little hands (easier for kids to use themselves). We use this single-herb medicine for bruises, mild pain, mild trauma, growing pains, sprains, strains, nerve pain, herpes, and more. For growing pains… When my middle child was younger he would wake up many times at night complaining of his legs hurting (he is now over 6 feet tall). I would grab the saint john’s wort oil and spend about 5 minutes massaging it into his legs. That is all it took for him to feel more comfortable and get back to sleep. For tail-bone trauma… Roller skating with my kids, I fell right on my tailbone. Of course, I didn't have my first aid bag with me that day and so didn’t have my saint john’s wort oil. After enduring the 45-minute ride home in the car I was in agony. I couldn’t sit or move without pain. I laid in bed rubbing the oil into my tailbone area and within 20 minutes I was up and moving around again. Repeated applications throughout the day had me pain-free by the end of the day. For cold sores… I combine Saint John's wort, lemon balm, and licorice in a liniment formula for cold sores. At the first sign of the tell-tale tingling sensation, I start applying liberally throughout the day. This is usually enough to stop an outbreak before it starts. If I miss the first signs and develop a full-blown cold sore it will take a little longer to clear up, but the liniment still helps to relieve the pain and heal the outbreak faster than if it were not used. Sprains and strains… I have used saint john’s wort oil several times for myself and family members to help heal sprained ankles or strained wrists. Repeated applications of the oil help to bring down swelling, ease pain, and speed healing. The oil is massaged into the joint several times a day, or a compress can be used to wrap the joint and allow the infusion to soak into the tissues. Shingles… While I have not experienced shingles myself, I have given saint john’s wort oil to others with painful shingles outbreaks on their faces. They have reported back that the oil noticeably helps reduce pain and seems to speed healing. Skin issues… I add Saint john's wort to an all-purpose salve formula I have been making for years called 7healers salve. Saint john’s wort lends its anti-inflammatory, vulnerary, analgesic, and antiseptic properties to this formula. Other herbs in the formula include yarrow, violets, plantain, yellow dock, echinacea, and comfrey. This salve has proved helpful for minor abrasions, bruises, bug bites, rashes, and other minor skin issues. Growing and Harvesting I have planted Saint John’s wort many times in my garden and it never seems to stick around for more than a few years. I’m not sure why. But I have found it to be the case with several plants that they are just not happy in my little microclimate, and though I may successfully nurture them through a season or two, they ultimately disappear. For Saint John’s wort, I suspect that my soil is just too rich and moist. When I find the plant growing wild, it is often on the side of the road, in waste places where the soil is hard, compact and depleted, or in very recently cleared areas where the first pioneer plants are quickly covering the earth and repairing the damage. In these instances, Saint John’s wort is often found with other weedy medicinals such as mullein, yarrow, plantain, and dandelion. They all grow in profusion for a season or two and then are replaced by other herbaceous plants, bracken, shrubs, and then eventually trees. In these observations, hypericum seems to play a role as one of the first plants to heal disturbed areas. Once the soil begins to build, they are no longer needed. As a result of this, although I do continue to plant a few plants in the garden each year, the bulk of my medicine making of hypericum comes from wildcrafted plant material. I start keeping an eye out for wild plants in early June. By then they are tall enough to recognize among the other weeds from their stiff stems and small, ovate, opposite leaves dotted with seeming pin holes. Once I identify a few good areas that have an abundance of plants, are not on private property (unless I have permission) or in a public park, and are not along the roadside (eww, exhaust) or in an area that is sprayed with chemicals (all these disqualifiers don’t make it easy), I’ll come back in late June or early July when the plants are still primarily in the bud stage, but just beginning to flower, and begin harvesting. The good thing about wildcrafting Hypericum perforatum is that it is not a native or endangered plant, so you don’t need to worry about overharvesting and depleting the populations. Plus, since we are harvesting the flower buds, the plant remains alive to continue to grow and spread through their rhizomes. I also like to leave some flowers to go to seed and continue to produce more plants. To harvest Saint John’s wort, I use my snips to prune the top 2 to 3 inches of the stalks. This method harvests the flower buds, and also some leaves as well (I know most sources say to only harvest the flower buds, but I have talked with other herbalists that use the leaves as well, and in all the years I’ve been doing it this way the medicine has still been excellent, if a little less red in color). I always say a little prayer of thanks to the wild plants for the gift of their medicine, with a promise to use it to ease suffering. Once back home I prepare the plants for medicine making. Saint John’s wort doesn’t retain its vitality well once dried (though I have heard some debate about this recently in the herbal community), so I will usually make medicine with fresh, freshly wilted, or freshly dried plants. For tincturing, I will almost always make a fresh plant tincture as soon as the plants are back home (see ratio recommendations above). For infusing in oil, I have moved away from using fresh plants to either spreading them on a screen and wilting overnight or drying in the dehydrator for one day before combining with oil. Wilting them severely decreases the water content, reducing the risk of going bad. Any water left once the oil is strained can be removed by allowing the infused oil to rest overnight (the oil and water will separate with the water sinking to the bottom) and then pouring off the oil the next day, leaving the water behind. This step can be eliminated though, simply by drying the plant material first and then infusing in the oil once dry. Although almost all the literature warns to only use fresh plants for medicine making, the freshly dried plants are still vital and strong medicine. Just don’t let them sit around for a while before getting to your oil. Cautions and considerations: Use caution when using externally in areas exposed to sunlight, as the fresh plant is phototoxic and can lead to sunburn. Avoid taking Saint John’s wort internally if using SSRIs or other medication that is processed through the P450 pathway in the liver. Saint John’s wort increases the efficiency of this detox pathway and can lead to medications being processed out of the body quicker than normal. This includes birth control pills, blood thinners, non-sedating antihistamines, calcium-channel blockers, some antibiotics, some antifungals, some chemotherapeutic drugs, antiepileptic meds, and medication that suppresses the rejection of organ transplants. Avoid in cases of severe depression or bipolar. References: Easley, T., and Horne, S. (2016). The Modern Herbal Dispensatory. California: North Atlantic Books Wood, M. (2008). The Earthwise Herbal (Old World). California: North Atlantic Books Stansbury, J. (2020). Herbal Formularies for the Health Professional, Volume 4 Neurology, Psychiatry, and Pain Management. Vermont: Chelsea Green Publishing Felter, H. W. (1922). The Eclectic Materia Medica, Pharmacology and Therapeutics. Cincinnati, Oh. Eclectic Medical Publications. Hoffman, D. (2003). Medical Herbalism. New York: Healing Arts Press. Keville, K. (1998). Herbs for Health and Healing, A Drug-Free Guide to Prevention and Care. California: Rodale Press. McIntyre, A. (1996). Flower Power, Flower Remedies for Healing Body and Soul Through Herbalism, Homeopathy, Aromatherapy, and Flower Essences. New York: Henry Holt and Company Grieve, M. (1931). A Modern Herbal. New York: Dover Publishing Knab, S. H. (1995). Polish Herbs, Flowers & Folk Medicine. New York: Hippocrene Books Storl, W. (2012). The Herbal Lore of Wise Women and Wortcunners. California: North Atlantic Books. Bone, K., Mills, S. (2013). Principles and Practice Phytotherapy. New York: Elsevier. Commonwealth Herbs St John’s wort herb of the week page, retrieved 5-10-22, https://commonwealthherbs.com/st-johns-wort-herb-of-the-week/ Saint John’s Wort, Ancient Herbal Protector, from Christopher Hobbs, PhD, retrieved 5-11-22 from https://www.christopherhobbs.com/library/articles-on-herbs-and-health/st-johns-wort-ancient-herbal-protector/?fbclid=IwAR3qCEydTmKFwhZbHZCSDjposl5l0g2IMrYiycOU61J0QbBIWAOKP1QMLno Saint John’s Wort Wikipedia page, retrieved 5-8-2022, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Hypericum_perforatum Al-Akoum, M., Maunsell, E., Verreault, R., Provencher, L., Otis, H., Dodin, S. (2009) Effects of Hypericum perforatum (St. John's wort) on hot flashes and quality of life in perimenopausal women [The Journal of the North American Menopausal Society]. Retrieved May 12, 2022, from https://journals.lww.com/menopausejournal/Abstract/2009/16020/Effects_of_Hypericum_perforatum__St__John_s_wort_.15.aspx Mi-kyoung, Y., Du-Woon, K., Kyu-Shik, J., Mi-Ae,B., Hwan-Seon, K., Jin,R., Hyeon-A, K. (2018) St. John's Wort (Hypericum perforatum) stimulates human osteoblastic MG-63 cell proliferation and attenuates trabecular bone loss induced by ovariectomy [Nutrition Research and Practice]. Retrieved May 12-22, from https://synapse.koreamed.org/articles/1051498 Kumar, V., Singh, P.N., Bhattachara, S.K. (2001) Anti-inflammatory and analgesic activity of Indian Hypericum perforatum L. [Indian Journal of Experimental Biology]. Retrieved May 12-22, from http://nopr.niscair.res.in/handle/123456789/23716 Rodríguez-Landa, J.F., Contreras, C.M. (2003). A review of clinical and experimental observations about antidepressant actions and side effects produced by Hypericum perforatum extracts [Phytomedicine]. Retrieved May 12, 2022 from doi:10.1078/0944-7113-00340

7/6/2022 0 Comments Peach Monograph

History: There is some dispute about whether the peach tree is native to the Middle East or to China. It was mentioned by Confucius in the fifth century BC, and by Theophrastus in 392 BC. Peach moved from the Persian Empire into the Roman Empire and eventually into Europe. In the late 1600s, peach stones were brought to the New World by the Massachusetts Bay Colony, where they seeded plantations throughout the colonies. Historically, peach was used to staunch bleeding, for coughing and loss of voice, and to aid with sleep and rest during illness. It was used as a restorative for both the digestive system and the nervous system, and for inflamed conditions of the lungs and urinary system. Peach was also used to improve the complexion and treat warts and acne. The eclectics used peach for gastric irritation with abdominal tenderness and for vomiting. Felter writes that it is not as effective as cherry for coughing, but more effective for digestive irritations. He recommends the cold infusion over the tincture for this. Jethro Kloss has used peach for morning sickness, vomiting, whooping cough, dyspepsia, scalding urine, and baldness.

Leaves are calming for both the nerves and for hot, inflamed conditions. They can be helpful with spasmodic cough, especially with dryness. Other hot conditions where the leaves may be useful include hot fever (especially with lack of sweat), hot respiratory conditions, hot menopausal conditions (especially with dryness), and hot digestive conditions (indigestion, ulcers…). Jim McDonald recommends peach for people with heightened auto-immune flare-ups, or for severe food sensitivity reactions. Doctor Christopher writes that the kernels, when boiled in vinegar could restore hair growth in cases of baldness, and that the gum, which the tree exudes, could be used to treat cough, hoarseness, and loss of voice. He also writes that in China the gum is used as a “sedative, alterative, astringent, and demulcent”. Studies: In a 2007 study, polysaccharides from marshmallow, burdock, and peach were tested for antitussive effectiveness against medically-induced coughing in cats. It was concluded that the antitussive properties of these plants were higher than that of the non-narcotic drug used for coughing in clinics. In a 2010 study, researchers studied the anti-inflammatory effects of the ethanol extract of peach fruits. Peach extract reduced the histamine release from mast cells after an allergic reaction was induced. The researchers concluded that the “inhibitory effect of FPP on pro-inflammatory cytokines was nuclear factor (NF)-κB dependent”.

Personal observations: In collecting peach leaves for tincture from a tree in the very back of my garden, I had to move through a patch of flowering ragweed, which I am very allergic to. I knew it would cause a reaction, but I was determined to harvest my leaves. I carefully pushed past the stalks, trying to disturb the pollen as little as possible, and harvested my leaves quickly, then headed back to the house. By the time I got inside I was having a full-blown reaction… inflamed sinuses, itchy eyes (I wanted to scratch them out), constant sneezing, and coughing. I could not work like this, so I picked up a book to read about peach while I waited for my reaction to subside. In reading Matthew Wood’s pages on peach, I came across these words… Because of the sensitivity of tissues in a dry, hot state, peach is well suited to allergies and autoimmune diseases, either directly as a curative or as an assistant. I had never thought of using peach for allergies before, but this made sense since an allergic reaction is essentially a hot, inflamed condition. I immediately took 3 fresh leaves from my harvesting basket and simmered them for 5 minutes in some water. After about 10 minutes of sipping the tea, I could feel everything calming down. Another 10 minutes and I felt well enough to get back to work making my tincture. I love experiences like this when the act of working with the plant teaches us more about its medicine. Cautions and considerations: As with other trees in the rose family, the peach tree contains cyanogenic compounds and requires some caution with its use. Low doses are harmless and the toxin is not cumulative in the body. But high doses can be extremely toxic, leading to rapid pulse, spasms, nervousness, numbness of the throat, unconsciousness, and death. The tea should never be left standing too long and careful attention to dosing given. However, this toxin is also an important part of the medicine of peach and should not be feared, but used carefully and only when needed. Since cyanogenic compounds work by slowing the action of the Krebs cycle, peach should be used with caution or avoided in people with mitochondrial dysfunction. References: Sutovska M, Nosalova G, Franova S, Kardosova A. The antitussive activity of polysaccharides from Althaea officinalis l., var. Robusta, Arctium lappa L., var. Herkules, and Prunus persica L., Batsch. Bratisl Lek Listy. 2007;108(2):93-9. PMID: 17685009. Online class through Eclectic School of Herbal Medicine, Theory and Application of Traditional Western Energetics, with Matthew Wood, Thomas Easley, and Jim McDonald. Wood, Matthew. 2008. The Earthwise Herbal, A Complete Guide to Old World Medicinal Plants. Berkley, CA. North Atlantic Books. Christopher, John. 2010. Herb Syllabus. Springville, UT. Christopher Publications. Kloss, Jethro. 1939. Back to Eden. London Publishing House. Felter, H. W. 1922. The Eclectic Materia Medica, Pharmacology and Therapeutics. Cincinnati, OH. Eclectic Medical Publications. Shin T, Park S, Yoo J, Kim I, Lee H, Kwon T, Kim M, Kim J, Kim S. Anti-allergic inflammatory activity of the fruit of Prunus persica: Role of calcium and NF-κB. Food and Chemical Toxicity. 2010. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.fct.2010.07.009

6/4/2022 0 Comments Meadowsweet Monograph

Parts used: leaves and flowers, harvested when in flower Taste: bitter, astringent, sweet History: Meadowsweet has a long history of use in Europe where it was often used as a strewing herb in summertime, along with other aromatic herbs, to release fragrance when trod upon and hide unpleasant odors. The name Meadsweet was common in the 14th century when it was used in the making of mead, or honey wine. Herbalist John Gerard, writing around 1600, claimed that meadowsweet was useful for treating boils, malaria, burning and itching eyes (the distillate), and to “make the heart merrie”. Maude Grieve, writing in the 1930s, states that it is helpful for suppressed urination, edema, and diarrhea (especially in children).

Clinical uses: Meadowsweet excels as a digestive system normalizer. It is helpful in cases of indigestion, even when there is belching and bloating. David Hoffman writes that meadowsweet “protects and soothes the mucous membranes of the digestive tract, reducing excess acidity and easing nausea”. It can be used both as an antacid and in cases of over alkalinity. This can be especially helpful for folks taking commercial antacids, which suppress stomach acid. Because stomach acid plays an important role in digestion and protecting the GI tract from infection, meadowsweet offers a better alternative for symptom relief. Its astringent properties make it useful for cases of diarrhea. And though large doses may cause nausea, smaller doses are helpful for settling an upset stomach. Meadowsweet is also helpful in healing stomach ulcers. Whereas the isolated or synthetic salicylic acid found in aspirin can cause ulcers, this constituent in the whole plant is buffered by the plant’s other properties, making it not only safe but anti-inflammatory and healing to the stomach lining.

Externally, meadowsweet can be used as a wound antiseptic and to promote healing. It may also be helpful to reduce acne and to treat boils. Dosage and method of delivery: Regular infusion or standard infusion: up to one cup taken up to 4 times a day. Tincture: fresh leaf and flower (1:2, 95% alcohol): dried leaf and flower (1:5, 50% alcohol), 1 to 5 mls. up to 4 times a day. Hydrosol: one tablespoon diluted in water taken up to 4 times a day. Capsules: 1,000 to 2,000 mg up to 3 times a day. Personal observations: I have had patches of meadowsweet growing in the garden for many years. It is such a beautiful plant, even before it flowers. When it does flower, the clouds of sweetly scented blooms attract so many pollinators. I really do have a hard time harvesting this plant. I don’t want to cut down those flowers and take all that beauty out of the garden and away from the insects that love it so much.

Cautions and considerations: Large doses can cause nausea and vomiting. Avoid using it with children experiencing fevers. Avoid in cases of salicylate sensitivity.

References: Easley, T., and Horne, S. (2016). The Modern Herbal Dispensatory. California: North Atlantic Books Hoffman, D. (2003). Medical Herbalism. Rochester, Vermont. Healing Arts Press. Wood, M. (2008). The Earthwise Herbal (Old World edition). Berkeley, California: North) Atlantic Books. Grieve, M. (1982 reprint). A Modern Herbal. New York: Dover Publications. Bone, K. Mills, S. (2013). Principles and Practice of Phytotherapy. Elsevier Ltd. Filipendula ulmaria - Wikipedia. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Filipendula_ulmaria. retrieved July 2, 2021 |

AuthorWrite something about yourself. No need to be fancy, just an overview. Archives

November 2022

Categories |

Search by typing & pressing enter

RSS Feed

RSS Feed